Tarzan: Jungle King of All Media

This article was written: August 17, 2013 – September 1, 2013 and was to appear in the magazine “Alter Ego,” but failed to see print due to unforeseen circumstances. All images used in this article are in the public domain or are personal scans from the author’s collection.

I do not say the story is true, for I did not witness the happenings which it portrays, but the fact that in the telling of it to you I have taken fictitious names for the principal characters quite sufficiently evidences the sincerity of my own belief that it may be true. –Edgar Rice Burroughs, “Tarzan of the Apes,” All-Story Magazine, October, 1912

And so begins a “strange tale” told by a narrator, coming from an anonymous someone who, according to the author, had “no business telling it.” But aren’t we glad he did?

Consider the legacy. Tarzan (white skin) of the Mangani (the Great Apes) is among the greatest fictional heroes of all time, rivaled, perhaps, only by Sherlock Holmes. The character has appeared in pulps, books, silent films, movie serials, and feature films – there have been more Tarzans than James Bonds – television series, daily and Sunday newspaper strips, and comic books. Tarzan’s latest conquest is the internet, in an online adventure strip written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Tom Grindberg.

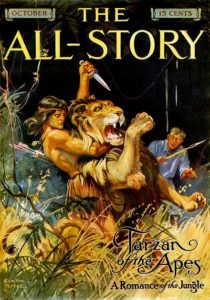

Tarzan’s first appearance, in the October 1912 issue of The All-Story (Wikipedia)

Tarzan is indeed the King of All Media. Sometimes, it’s the Tarzan written by Burroughs, known as John Clayton, born to John and Alice (Rutherford) Clayton, Lord and Lady Greystoke, cultured and educated, and who had a son named Korak and who never, ever said “Me Tarzan, you Jane.” Sometimes, it’s the Hollywood version in which Tarzan has a son named “Boy” and a pet chimp named “Cheeta.” Through it all, the power of the concept — and the character — of Tarzan has flourished. Virtually everyone on the planet knows who he is.

Tarzan of the Apes was the first story, written from December 1, 1911 through May 5, 1912. The second story was The Return of Tarzan, published as a seven-part serial in the June through December 1913 issues of New Story Magazine. From there it continued through Tarzan and the Madman – the twenty-third book in the series. When ERB passed away on March 19, 1950, he left behind an unfinished, 83-page, typewritten manuscript. Texas writer Joe R. Lansdale completed the tale and it was published in 1995 by Dark Horse Books as Tarzan the Lost Adventure.

A 1914 publication of Tarzan of the Apes (originally from 1912). (Wikipedia)

On film, the roster of titles, formats and lead actors far outshines James Bond, Harry Potter, or any other hero. Beginning with Otto Elmo Linkenhelt (Elmo Lincoln), there were seven silents. Of the major Tarzan features, there were twelve starring Johnny Weismuller, five with Lex Barker, six starring Gordon Scott, two with Jock Mahoney, and three with Mike Henry. Along the way there were many unauthorized Tarzan serials and features with such actors as Larry “Buster” Crabbe, Herman Brix and Glenn Morris. In a 1966 article, writer John McGeehan listed thirteen Tarzans – not counting TV’s Ron Ely. Since then, there have been several more movie Tarzans, failed TV series, animated films – and even Disney has gotten into the Tarzan business.

“The Apes Are Coming” — Tarzan in Comic Strips

Sixteen years had passed since the first Tarzan story had seen print and it was now 1928 – time for Tarzan to conquer another medium, the daily and Sunday comics in the nation’s newspapers. There are many accounts of how it started, and one of the best comes from famed ERB historian and collector Camille E. Cazedessus, Jr. in his article “Lords of the Jungle” (featured in Don Thompson and Dick Lupoff’s The Comic-Book Book 1973/1998). According to the article, the editors at the Metropolitan Newspaper Syndicate were considering a grand experiment: could an adult-oriented, serialized, non-comical comic strip work in the daily and Sunday comics section of the day’s newspapers? They wanted realism in the drawings and they needed an exceptional artist to pull it off. They offered the job to Harold R. Foster.

Some historians wonder why Foster, with an apparently successful career in advertising and magazine art, ever took the job in the first place.

The late Bill Blackbeard (founder-director of the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art), writing in the introduction to NBM’s Tarzan in Color hardback series of Sunday page reprints, Volume 2 (1993) opines that Foster must have thought it over quite seriously: “He has said he originally regarded comic strip work as a low level creative expression, and undertook the daily strip-text adaption of the Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes primarily as a passing challenge to his imagination and as a friendly assist to fellow advertising executive Joe Neebe, who wanted to syndicate the adaption to newspapers.”

Dust-jacket illustration of Tarzan of the Apes first edition. (Wikipedia)

Foster did take the job – and later left and then returned to it, perhaps due to the realities of the Great Depression that surely were not kind to advertising agencies. The strip must have – at the least – provided a steady income.

And, as we learn in the NBM edition, it became quite inspirational to a young Ray Bradbury. “How do I love Tarzan of the Apes as illustrated by Hal Foster in the midst of my 10th year in 1930?” he asks in the foreword. Then, he counts the ways. And we learn that at the time of this writing (August 20, 1992), the famed fantasy writer still had his collection of Foster Sunday pages, neatly stored in an abandoned clothes-closet. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Back to 1929, when the syndicate was about to launch the dailies…

Cazedessus tells us there was no large-scale promotional campaign – just a few ads in newspapers that would carry the strip saying, “The Apes Are Coming.” Those first few newspapers printed the first Tarzan segment on January 7, 1929, well received at the time and, to this day, still highly regarded by ERB fans. Even so, with Foster somewhat disinterested and busy on other projects, Rex Maxon was brought in to do the second story, which adapted The Return of Tarzan.

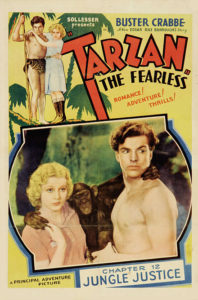

Tarzan, as depicted by Buster Crabbe in the film serial Tarzan the Fearless (Wikipedia)

Cazedessus’ long article is complemented by an equally informative article by John McGeehan entitled “TARZAN and how he grew OR whatever happened to Jane Baby?” This heavily researched piece ran in the April 1966 issue of the late Tom Reamy’s wonderful science-fiction fanzine, Trumpet. McGeehan was a well-known trivia buff and the art credits and the data on dates and strip numbers that follow (up until the time the article was published) come from him. We have extrapolated from that, based on additional data available on-line. By the way, if you knew Tom Reamy – and I did – it’s not hard to imagine that the fascinating title of the article was his idea, though we’ll never know for sure.

The first two stories ran 6-days-a-week for ten weeks. These early stories were not dated, but instead carried a code letter and number. The letter designated the story and the number referred to each individual strip. So “B-45” was the 45th strip in the story Beasts of Tarzan. The first stories (Apes and Return) had a single row of panels, with narration below the illustrations. Later on, a six-episode condensed version of the first story, drawn by Foster, was made available to newspapers that wanted to pick up the strip, but didn’t want to start cold.

There were twenty-six letter-coded stories, not counting Tarzan of the Apes, which was not letter-coded. A through R were illustrated by Rex Maxon; S through V by William Juhre; and W through Z by Maxon. “Z” was the first original script – “The Fires of Tohr,” also the title of the second Dell tryout comic that was still years away. Following this story, the scripts were not titled, but carried numbers. Number 1 was dated August 28, 1939. The text was moved into the illustrations and remained that way until word balloons started in 1958.

Artists for the numbered strips were: Rex Maxon (1-2508); Burne Hogarth (2509-2616); Dan Barry (2617-2892); John Tehti (2893-2958); Paul Reinman (2959-3276); Nick Cardy (3277-3414); Bob Lubbers (3415-4500); and John Celardo starting with 4501 for a total of 4,350 dailies taking us to number 8850. Early writers on the dailies included Dick Van Buren and Bill Elliot.

There came a time during the run of these dailies when there was simply no more original Burroughs material to adapt. According to Cazedessus, after The Return of Tarzan, a series of longer adaptions had run – 14 to 21 weeks in duration – based on nine more Burroughs stories. But by the end of Tarzan and the Ant Men in 1932, the Burroughs well was running dry. In mid-1932, Maxon and his collaborators (possibly George Carlin and/or Don Garden) began a long serial – a 40-week adaption of Tarzan the Untamed that would become the first story to deviate substantially from what Burroughs had written. The new villains were Communists instead of World War I style Germans – a sign of the changing times.

Maxon was on a roll, and in March of 1931, he was handed the art chores for the new Tarzan Sunday page. Now, Tarzan could be read and enjoyed in full color – but the stories were lacking. The first concerned two children, Bob and Mary, who were menaced by apes and then by pirates and saved by Tarzan. The strip needed a boost and help came – with the return of Hal Foster. “Caz” tells us that Foster “…moved in with a bang!”

Foster immediately took the strip back to its Burroughsian roots, with Tarzan battling gangs of apes and rescued by his old friend Lt. Paul D’Arnot, a Burroughs character from the first story. ERB historians say the Sunday page prospered, far outshining Maxon’s dailies. However, there was a problem — and it concerned Foster himself who desired to draw a character of his own creation. So, after almost 300 Sunday pages, Foster left to begin the adventures of Prince Valiant in February 1937. The final Foster Tarzan page saw print on May 2nd.

With Foster gone, the second great Tarzan artist – Burne Hogarth – began his run. Hogarth, just 26 at the time, gave Tarzan a vibrant, larger-than-life feel, bringing his adventures to their full potential on the page.

Some historians, noting the amazing layouts, kinetic panels, and exciting action sequences, will tell you that Hogarth actually surpassed even the great Hal Foster. In 1972, long after leaving the ape-man, Hogarth returned to the drawing board to produce a brand new Tarzan of the Apes for Watson-Guptill Publishing – a hardcover containing 160 pages and 122 pages of full-color illustrations. It was published in 11 languages.

Hogarth followed with another book, Jungle Tales of Tarzan, in 1976, [according to Wikipedia] “using new techniques such as hidden, covert, and negative space imagery with inspired color themes into a harmonious visual description, a pinnacle of narrative art.”

Credits on the Sunday page are Rex Maxon (1-28); Hal Foster (29-321); Burne Hogarth (322-768); Reuben Moreira (769-856); Burne Hogarth (857-1014); Bob Lubbers (1015-1198); and John Celardo beginning with 1199. Celardo began the Sunday strip on February 28, 1954 handling 724 Sunday strips, which would have taken him through strip number 1922. At that time, Tarzan was appearing in 225 newspapers in 12 different countries. Celardo drew Tarzan until the great Russ Manning succeeded him.

And the apes kept right on coming!

Of course, it was the comic strips that led to Tarzan’s early appearances in comic books. Here’s a listing of the comics devoted to reprints of the newspaper strips, compiled with data from McGeehan and Overstreet:

- The Illustrated Tarzan Book #1 (1929/Grosset & Dunlap) Perhaps the first Tarzan comic book, reprinting the initial Foster story

- Tip Top Comics #1-162 (April 1936 – June 1941/United Features Syndicate) and #171-188 (November-December 1951 – September-October 1954) — Foster (#1-40, #45-50); Maxon (#41- 43); Hogarth (#’s 59, 57, 62); Lubbers (#171-188); some issues with new covers by Paul F. Berdanier

- Dell Comics series of black & white large feature books 5th edition (1938) Foster reprint with new art by Henry E. Valley

- Comics on Parade #1-29 (April 1938 – August 1940/United Features Syndicate) – Dailies by Foster & Maxon

- Famous Feature Stories #1 (1938/Dell) – Six-page text story entitled “Tarzan and the Hidden Treasure” illustrated by Valley

- Crackajack Funnies #15-36 (September 1939 – June 1941/Dell) – Text stories from Lord of the Jungle except for #26 and 35

- Popular Comics #38-43 (April-September, 1939/Dell) — Two or three pages of text with un-credited illustrations

- Single Series #20 (1940/Dell) – Foster’s “The Egyptian Adventure”

- Sparkler Comics #1-92 (July 1941 – March-April 1950/United Features Syndicate) — Sunday reprints by Hogarth except issues #87-89 [The Overstreet Price Guide lists #86 as the last Tarzan]

In 1982, Nantier/Beall/Minoustchine Publishing (NBM) of New York created the Flying Buttress Classics Library imprint for the purpose of reprinting classic strips. It came out with Treasury-sized, hardback editions entitled Tarzan In Color, complete with dust jackets, reprinting the Sunday pages. The 18-volume series covered Foster’s work from September 27, 1931 until 1937, and Hogarth’s work from May 9, 1937 until 1950, skipping the two-year interregnum from 1945 until 1947.

Tarzan also appeared in several issues of March of Comics, a K.K. Publications (Western) giveaway; in Jeep Comics, from R.B. Leffingwell & Co., distributed to servicemen; and, of course, in Big Little Books. However, Tarzan’s heyday in comics, with all-new stories and art, got underway with a Dell two-shot in Four Color Comics that led to his first original, on-going series.

King of All Companies – Beginning with Dell

If we’d asked you, before you picked up this issue of Alter Ego, to name a hero with his own series in Dell, Gold Key, Charlton, DC, Marvel, Blackthorne, Malibu, Dark Horse, and Dynamite – you might have drawn a blank. Of course, only Tarzan has done that. The main reason is that, while characters like Superman and Batman are company-owned, Tarzan was creator-owned. So Burroughs or ERB, Inc. was free to make deals, change companies as contracts expired, and pursue legal action when non-licensed companies put out their own product.

The first licensed deal for new stories and art went to Dell and kicked off in 1947 with Four Color Comics #134 (“Tarzan and the Devil Ogre” and #161 (Tarzan and the Fires of Tohr”). This new series, written by Gaylord DuBois and illustrated by Jesse Marsh, was not strictly Burroughs-inspired. The basic premise – the white jungle lord in a world dominated by Great Apes and African tribes – was intact, but there were elements from the newspaper strips and certainly from Hollywood.

In Cazedessus’ “Lords of the Jungle,” the writer notes that by the third Dell issue (#1, following the two try-outs), DuBois had created a new and permanent jungle world that was different from what the newspaper strips had done:

“In this world, Jesse Marsh drew Tarzan as a pleasant-looking fellow living in a tree house with a brunette Jane and Boy. The movies had done their job: in the Jungle World, the film Tarzan had finally displaced Burroughs’ creation, bringing with him the companions and conventions of Hollywood.”

Yes, indeed, but many of the comics of the day, and especially Dell, were aimed at children. So, as Caz points out, the Burroughs Tarzan was a cultured and articulate nobleman, his Jane was blonde, and they live in a fine house with Korak who, himself, had a son – while the Dell Tarzan was still in many ways the movie stereotype.

In all fairness to DuBois, his Tarzan was not stupid, illiterate, or particularly uncultured. DuBois was simply working either with some degree of freedom, or with a company mandate to appeal to the teens and younger children likely to plop down a dime for a taste of jungle action. So it was “Boy” and not “Korak,” but there was never any usage of “Me Tarzan, you Jane.”

While Tarzan spoke in flawless English to advance the story, he was equally at home with the language of the Mangani:

“Kreegah!”* “Bundolo!”**

*Warning/Danger **Fight to kill

Dell even carried features to explain the language of the apes that was useful whether you happened to be Tarmangani or Gomangani. If kids in the late forties and fifties were sharp, they could be bilingual. No doubt, many became proficient at ape-speak.

DuBois worked to make the Tarzan comic exciting for his expected young audience. So he populated Tarzan’s jungle with lost worlds and strange lands, prehistoric creatures, and fascinating characters – building on what Burroughs had already created. Tarzan now rode on the backs of animal friends like Tantor the elephant (beginning in issue #6), Argus the giant eagle and Tarzan’s lion companion Goliath, or Jad-bal-ja, a Burroughs creation who had appeared in the ninth novel, Tarzan and the Golden Lion. There was also Bara the giant eland, the monkey Nkima who had appeared in the later novels, and various gryfs. DuBois brought Paul D’Arnot to the comics, as well as a paleontologist character named Alexander WcWhirtle.

In Tarzan #20, March 1951, the inside front cover featured a map in great detail of Tarzan’s Jungle World of Pal-Ul-Don, which we first visited in Tarzan the Terrible.

The Jesse Marsh version shows a great crocodile-infested swamp belt to the west and north; Dan-Lur, city of outlaw Ho-Dons; the deep jungle where dwell the cat men Ho-Dons; Li Pona, the white pygmies; A-Lur in the center of the map as capital of Pal-Ul-Don; Magnus, City of the Lost Legion; Valley of the Monsters where you can make out a triceratops (or “gryf”), a brontosaurus, and a T-Rex; Opar, the ancient city and Queen La; Tohr, the city of science from Four Color #161 and Queen Ahtea; Tor-O-Don the beast man; and a lot more. The map is on a scale of 1 inch = 40 miles. It’s printed sideways on a Golden Age comic page (about 6” x 8”) so Pal-Ul-Don might have been about 76,800 square miles – of pure adventure.

According to his Wikipedia entry, Gaylord McIlvaine DuBois wrote more than 3,000 comic book stories and comic strips as well as Big Little Books and juvenile adventure novels. He was an avid outdoorsman who wrote hundreds of Westerns, jungle comics, TV show adaptions and funny animals. He is credited with creating some of Western Publishing’s backup features such as “Captain Venture: Beneath the Sea,” “Leopard Girl,” and “Two Against the Jungle.”

DuBois excelled at animal stories and he was prolific, writing animal leading-characters such as Silver, Trigger, National Velvet and Lassie. He is said to have been a devout Christian and, as such, may have consciously instilled a strong moral compass into his stories. His Tarzan scripts were early examples of wildlife conservation and black people as sympathetic characters with heroic capabilities.

He took the cross-racial partnership to a new level in Tarzan #25, October 1951, with the debut of a backup feature entitled “Brothers of the Spear.” First drawn by Marsh, the brothers were Dan-El, a white man, and Natongo, the black son of a Zulu chieftain. In the first story, at the Feast of Spears, Natongo hits a bull’s-eye – only to see the shaft of his spear split by Dan-El’s subsequent throw. Dan-El suggests they become blood brothers and they do with a flick of Natongo’s knife. Blood thus mingled, they shared adventures together continuously through Tarzan #156, later serving as an early showcase for the acclaimed artwork of Russ Manning, and eventually getting their own title. The Gold Key series ran 17 issues from 1972 until 1976 with DuBois providing the scripts beginning with #2.

Gaylord DuBois was born on August 24, 1899 and passed away on October 20, 1993. He wrote Tarzan for Dell and Gold Key from 1946 until 1971.

Jesse Marsh was the first artist to produce original Tarzan material for comics. Though he was an early Disney animator and worked for years on the Gene Autry Comics, he will always be remembered for Tarzan. Marsh was born on July 27, 1907 and lived until April 28, 1966. He turned the Tarzan job over to Russ Manning in 1965 due his deteriorating health. Dark Horse named eleven volumes of its hardback archives in his honor: Tarzan: The Jesse Marsh Years.

One of the finest pleasures of the Dell era was the great covers that came in all varieties: line art, photos, paintings and various combinations. Marsh drew the early covers, including the two Four Color issues and the first seven of the ongoing series. According to the Dark Horse archives, Morris (Mo) Gollub drew the covers on issues #8-12. Issue #13 was a hybrid with movie actor Lex Barker and a chimp friend (probably Cheeta) occupying the bottom right quarter of the page, surrounded by six small illustrations. This pattern continued through issue #16, which was also the first to feature the credit “Lex Barker as Tarzan” in a small typeface at the bottom of the page. With issue #17, Barker’s photo fills the cover, and in slightly larger reversed type, the credit reads simply “Lex Barker.” Barker certainly looked the part on the covers and undoubtedly attracted a lot of attention on the spinner racks. His covers lasted through issue #54, March 1954. His reign as Tarzan was over, but Dell did not return to line art on the covers.

Instead, the publishers opted for spectacular, fully painted covers. Always un-credited and never signed, they were at least as striking as the Barker covers had been. But while Barker was usually posed in a tree with a knife in his mouth, or with a friendly animal, the painting format provided an opportunity for drama.

The first cover, issue #55, April 1954, had Tarzan in battle with a tiger – a very big cat – and as the animal is wrapped around the Jungle King’s torso, they are practically face-to-face, staring each other in the eyes. The second painted cover, #56, had Tarzan underwater, holding tight to the snout of a giant shark. Again, the Dark Horse archives credits these wonderful covers to Mo Gollub. It’s hard to know for sure. The Grand Comics Database (comics.org) credits Gollub with covers for #71 and #114. But the latter of these two covers has also been credited to the prolific George Wilson. The Database says Wilson painted #111, 112, 116, and 117 – but click on #116 and you’ll see that some historians attribute that one to Gollub. In fact, the Grand Comics Database lists several covers with both artists named and a question mark as to which should get the credit.

Assuming the experts are correct on their artist-ID of specific covers, Tarzan was a lucky jungle king to have both Gollub and Wilson. They created scenes that would have been difficult to stage with a movie actor; scenes such as on the cover of #59 in which Tarzan is riding on the back of a croc while holding the animal’s jaws apart. Barker might have called in his agent had he been asked to pose for that one. There were peaceful scenes, too. Issue #61 had Tarzan at home in the trees, smiling with two young chimps at play.

The painted covers generally stayed away from cover blurbs. The typical cover simply carried the full-page painting with the Tarzan logo, the Dell box in the upper left-hand corner, the month and price. However, something moved the editors to add a box to the cover of issue #72, September 1955, all in upper case, reading:

IMPORTANT

SEE DELL’S PLEDGE TO PARENTS

ON INSIDE FRONT COVER

Dell, generally Wertham-proof, didn’t seem to worry too much about attacks on the comic book industry, and none of the remaining painted covers carried any type of blurb at all. For the record, here is the statement that appeared in that issue:

A Pledge to Parents

The Dell Trademark is, and always has been,

a positive guarantee that the comic magazine

bearing it contains only clean and wholesome

juvenile entertainment. The Dell Code

eliminates entirely, rather than regulates,

objectionable materials. That’s why when

your child buys a Dell Comic, you can

be sure it contains only good fun.

“DELL COMICS ARE GOOD COMICS”

is our only credo and constant goal.

This pre-emptive strike might have turned off Bart Simpson – but still, it was good for kids to know that fighting a deadly shark was good, clean fun. That’s even if they never wondered how Tarzan and Jane got “Boy.” The painted covers ran through issue #79, April 1956, ending with a jungle scene of a benevolent Tarzan carrying a huge basket of fruit and allowing a baby monkey to sample the goods.

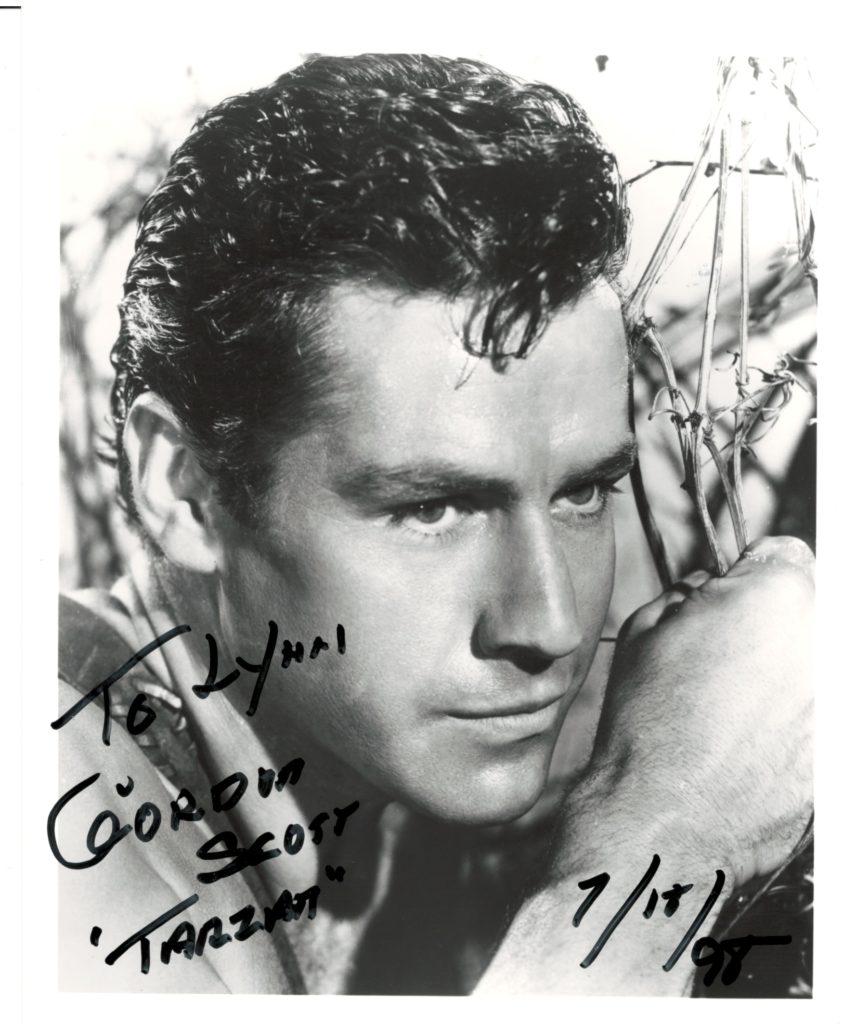

In 1955, Gordon Scott replaced Lex Barker as the reigning Tarzan of the screen, and, as of May 1956, replaced the long run of painted covers with those bearing his image. Barker’s first cover was a shot of the actor in a tree, with a long knife, sans caption or blurb. The first cover type didn’t show up until issue #92, May 1957, promoting the story “The Queen’s Luck.” From that point, all covers carried a story blurb through #107, though none of the covers seemed related in any way to the adventure inside. Issue #109, November 1958, returned the cover text, along with a new logo, a slightly elongated san serif typeface that lasted just one issue. #110, January 1959, returned to the traditional logo that Dell had been using, now “Still” 10 cents, and also marking the final cover appearance of Gordon Scott. Unlike Lex Barker, Scott never had a cover credit for his photos as Tarzan.

An interesting side note about Gordon Scott. I received a telephone call from a Waco dealer one evening, informing me that Scott was to appear at a convention in Dallas that weekend. It’s only a two-and-a-half hour drive from my home in Temple, so I decided to go and meet him. And there he was, 72 years old at the time, still looking pretty good and hawking 8×10 stills. I bought one and he signed it:

To Lynn

Gordon Scott

“Tarzan”

7/18/98

It was this convention that rekindled my interest in Tarzan comics. I bought all those I could find in-grade that day, and have never stopped combing the back issue bins.

Gordon Scott signed this still for me on July 18, 1998 at the Dallas Sheraton, Park Central. From the collection of Lynn Woolley.

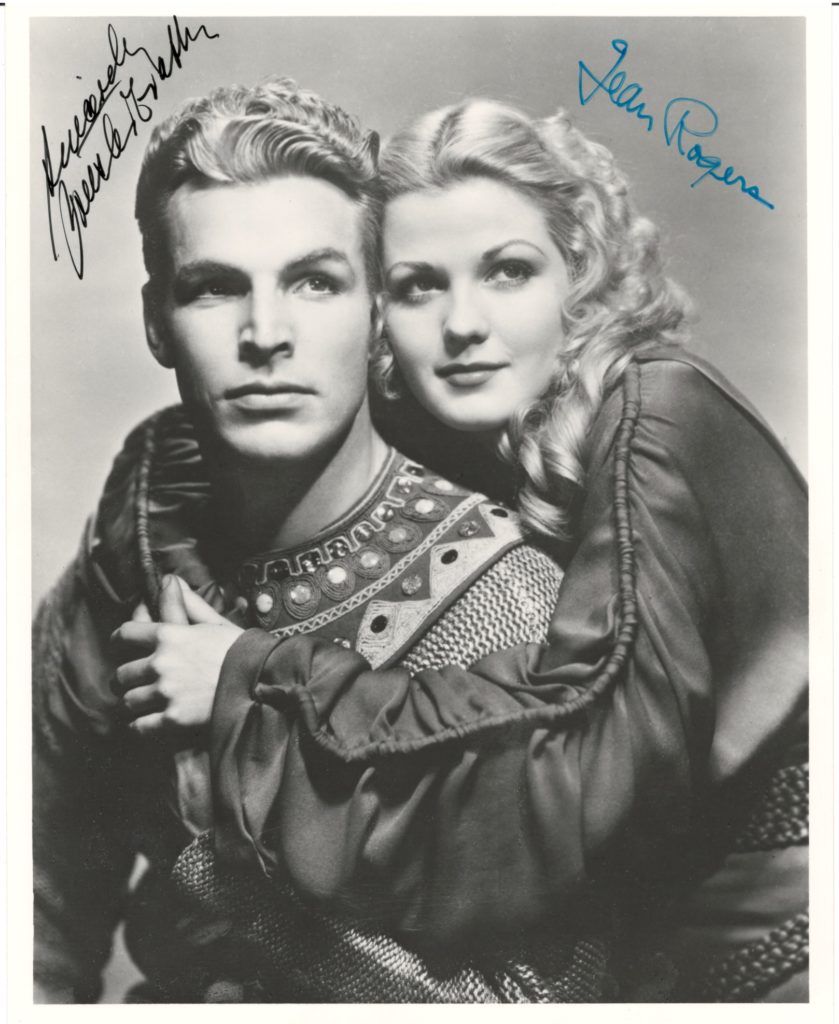

In checking my collection of stills, I remembered one other from a movie Tarzan: Buster Crabbe; although in my photo he’s not Tarzan, but rather Flash Gordon alongside Jean Rogers as Dale Arden. Each of them signed the still for me. That was at Dallascon ’77 in the now-demolished Baker Hotel.

With Tarzan #111, March 1959, the painted covers resumed via George Wilson as if the photo covers had never intervened. Tarzan is again shown in action, riding on the back of Gimla the crocodile, knife raised and ready to strike.

[The Grand Comics Database credits the cover of #111 to Wilson. Compare it to the cover of #59 – virtually the same scene, but credited to Gollub. You decide!]

With issue #121, the paintings began to occasionally feature prehistoric creatures. The Tyrannosaurus Rex on this cover is truly fearsome, with the caption, “Tarzan tracks the NIGHTMARE in the jungle.”

Buster Crabbe as Flash Gordon with Jean Rogers as Dale Arden — autographed for the author at Dallascon ’77. From the collection of Lynn Woolley

The look of the covers began to change. Issue #123 carried a 15 cents price tag, and #124 had a lot more type – along with another T-Rex. The Dell logo was a bit longer and looked like a postage stamp. The next issue, #125, had still more cover type promoting the story, a prize contest, and a “New, Exciting Dell Trading Post of Great Values.” With issue #127, Dell reverted to the classic look of the earlier painted covers, with just a story blurb at the bottom of then page. And so it would continue until the end. With the final two Dell issues, the logo lost the postage stamp look, and with #131, the price went back to 12 cents. And that was it for the Dell imprint.

The Dell Giants

Before we leave Dell Comics, we must mention the ten giant issues published from1952 until 1961. The first seven 25-cent issues were entitled Tarzan’s Jungle Annual and contained 100 pages. Beginning with the eighth issue, the page count went to 84, the number changed and so did the titles. Of those final three Dell Giants, the first was entitled Tarzan’s Jungle World, and the last two were Tarzan, King of the Jungle. The final three were not numbered in sequence due to Dell’s new system of numbering their giants as a single series, so they were listed as Dell Giant #25, #37, and #51.

Though the giants contained Marsh and some Manning artwork, they were different from the monthly titles in more than just size. They carried more features and games, and the painted covers deemphasized Tarzan, opting for generic jungle scenes. Lex Barker did appear on the first two covers, but only in thumbnail shots. On most issues the “Edgar Rice Burroughs” credit was moved to the bottom of the cover, in smaller type than you’d see on the monthlies.

The first Dell Giant issue (#25) retained the cover format of the earlier seven with an elephant stampede prominent – but no sign of Tarzan. Once the name changed to Tarzan King of the Jungle, the ape-man was back on the covers, about to spear a renegade rhinoceros (#37) and riding on Tantor the Elephant (#51).

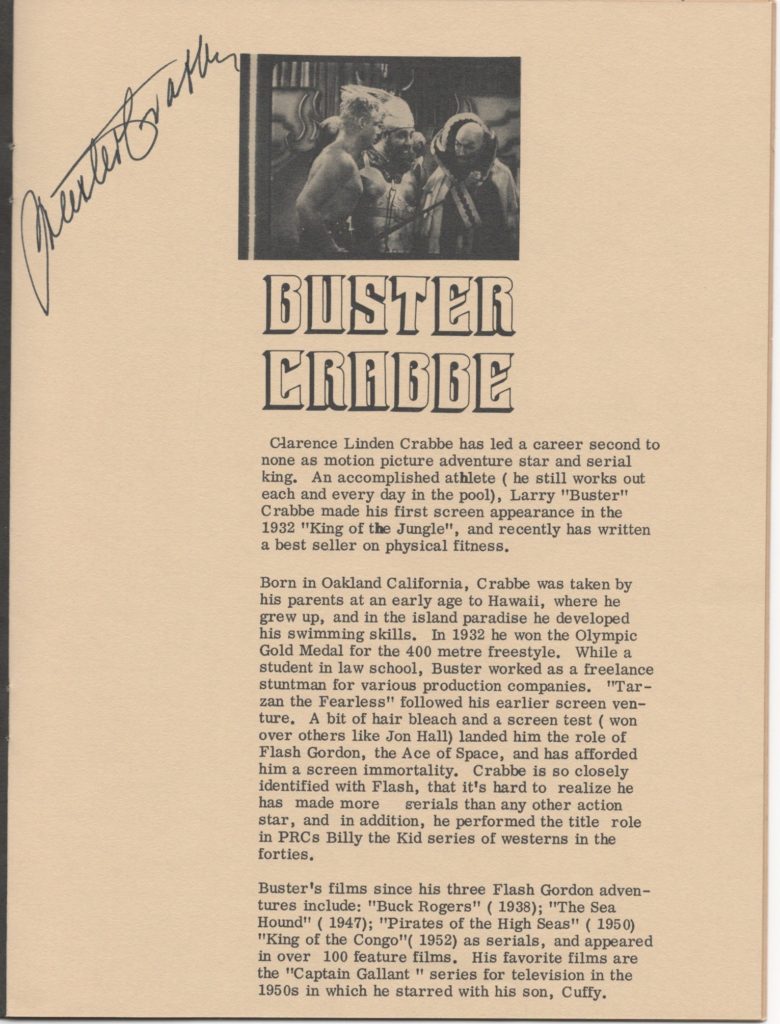

Buster Crabbe and jean Rogers adorning the cover of “Dallascon ’77” at the Baker Hotel in downtown Dallas. Color by Gary Tiner. From the collection of Lynn Woolley

Through two try-outs, 131 monthly issues, ten giants, and several March of Comics editions featuring Tarzan, Dell had been as good as its slogan: these Dell Comics were good comics. Writing in the Comic Book Price Guide, 5th Edition (1975), Burroughs collector Kevin B. Hancer noted, “The role of Dell and Jesse Marsh have, respectively, been overlooked by comics historians. Exhibiting production quality well above average, Dell produced a tremendous number of wholesome, quality comic books for the juvenile market.”

Indeed they did. As a very young reader, I would collect the tops from milk bottles or cartons produced by Superior Dairies and send them in for a free comic. The first time I did that, the postman who picked up the envelope joked with my mom and me about whether he’d actually make sure that the tops were delivered. He may or may not have seen to it, but I had ordered a Tarzan comic and it never showed up in the mail. But I have the last laugh. No matter what that mid-fifties issue was, I have it now!

Bio signed by Crabbe at Dallascon ’77. From the collection of Lynn Woolley.

The Big Split: Gold Key Takes Over

The story of Gold Key begins, of course, with Dell, for whom it produced and packaged comics for years as Western Printing and Lithographing. After business disputes led to a split, Western took control of most of the licensed titles and published them under the new Gold Key imprint. That included the ERB properties. One quick change involved the cover price of the books. As Mike Benton noted in The Comic Book in America – An Illustrated History, Western lowered the price on its books from Dell’s 15 cents back to 12 cents, which was the industry standard at the time. As noted above, the final Dell Tarzan had cost 12 cents as well.

Otherwise, being from the same publishing house, the look and feel of the books did not change too much at first. What separates the Gold Key Tarzan from its predecessor at Dell is the ascension of artist and later, scripter, Russ Manning whose incredible ink lines and devotion to Burroughs’ concepts makes him THE definitive creator to many fans.

George T. McWhorter, Curator of the Burroughs Memorial Collection and editor of Burroughs Bulletin, wrote a wonderful biography of Manning published in the Dark Horse collection of The Land that Time Forgot and The Pool of Time.

Russell George Manning, born in 1929 in Van Nuys, California (8 miles north of Tarzana), was already reading the Hogarth Sunday Tarzan pages in the Los Angeles Times when he was only 8 years old. After a year in junior college, he entered the Los Angeles County Art Institute. In 1950, this National Guard unit was activated due to the Korean War and he was sent to Japan where he served as a mapmaker and drew cartoons for his base newspaper.

McWhorter writes that it was in 1952 that Western Printing and Lithographing gave him his first job drawing the Jungle King. This story would appear two years after he had drawn it in March of Comics #114, June 1954.

Fast-forward to December of that same year and Tarzan #63 features a backup story of Tarzan and Boy entitled “The Canoe Safari.” This issue, according to Overstreet is Manning’s first work on Tarzan. At first glance, the faces look like Marsh’s work – clearly Manning was keeping with the style of the lead artist – but the line work and background stood out.

With Marsh in declining health, Manning took over Tarzan in 1965 with issue #155. He then created a series of adaptions from the Burroughs books, working from scripts written earlier by Gaylord DuBois. By this time, “Boy” was gone and Tarzan’s “real” son had moved to a new title: Korak, Son of Tarzan. This book, with DuBois scripts lasted from #1-#45 with art by Manning, Warren Tufts and Dan Spiegle.

The Tarzan comic was now called: Tarzan of the Apes.

In “Lords of the Jungle,” Cazedessus wrote: “To inaugurate the new phase in in the comic’s history, the Gold Key team went all the way back to the policy originally followed in Hal Foster’s daily newspaper strip almost 40 years earlier: Manning illustrated a series of 24-page adaptions of the original Burroughs Tarzan novels; some of the longer adaptions were extended to two or even three 24-page segments.”

The end product was indeed a wonder to behold. McWhorter calls Manning “one of the three greatest Tarzan comic-strip artists along with Hal Foster and Burne Hogarth.” Cazedessus says Manning’s natural talent and enthusiasm, coupled with his comic book experience made him a natural to take over the newspaper strip. United features Syndicate tapped him in 1967 to succeed John Celardo. He took over the dailies in December 1967 and the Sunday page in January 1968 – taking both to new heights.

Ah, yes. But that skips over a little bit of history that overlaps the comic book with the newspaper strip. So go back to late 1958 when the newspaper strip had become lackluster and childish. Burroughs fans grew impatient and a movement began, leading to the formation of the Burroughs Bibliophiles, a worldwide group of ERB enthusiasts, clamoring for a return to greatness. After Burroughs passed on in 1950, scant attention was paid to such trivial matters as trademarks and copyrights and (by November 1958) the quality of the newspaper output.

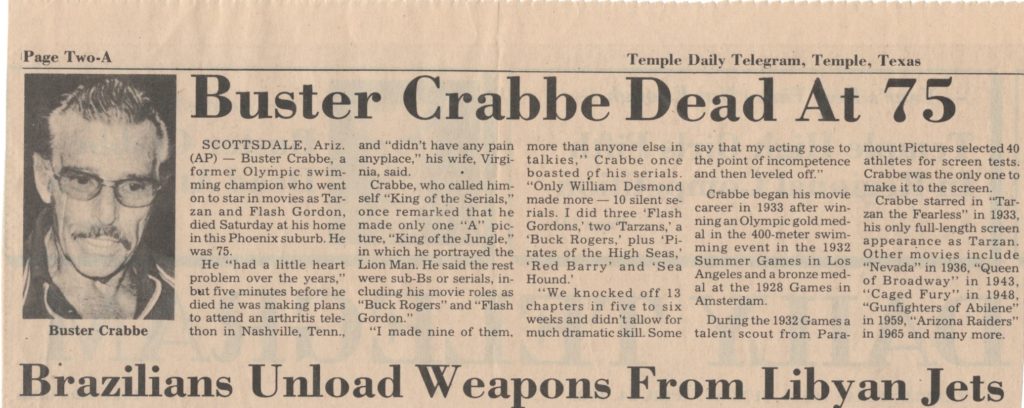

Buster Crabbe obit from the Temple Daily Telegram (Temple, Texas) April 24, 1983. From the collection of Lynn Woolley.

At that time, C.B. Hyde was president of the Burroughs Bibliophiles and he took the matter into his own hands. According to Cazedessus, Hyde contacted Celardo, who by now was handling the scripts as well as the art, and got him to look at some old Hogarth pages. So in the winter of 1962, apparently inspired by this encounter, Celardo returned to Tarzan’s roots by adapting an obscure short story entitled Tarzan and the Champion. But, after eleven years, he had grown tired of the strip and was thinking of retiring. He stayed on until Manning’s hiring in 1967.

Russ Manning took over the dailies in December of 1967 and the Sunday page in January 1968 – taking both to new heights. Manning, as you might expect, brought the same lush style and total respect for the source material that he had brought to the comics.

He brought back most of the Burroughs concepts such as lost cities and civilizations and he reintroduced newspaper readers to all the old characters and places – Korak, Tantor, Opar, La, Paul D’Arnot, Pal-Ul-Don, Pellucidar, and Jane! Fans were ecstatic – but the Force was not to be with them forever.

When Manning had a chance to take on the new Star Wars newspaper strip, he would eventually give up Tarzan. It took two years of Manning’s working on both strips before a young Gil Kane was brought in by UFS to work on Tarzan.

In 1974, two years after leaving the Tarzan daily strip, Manning wrote and illustrated four graphic novels:

- Tarzan In the Land That Time Forgot

- Tarzan and the Pool of Time

- Tarzan and the Beastmaster

- Tarzan In Savage Pellucidar

According to the McWhorter article, these stories were co-produced by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. and John-Claude Lattes for publication in England and elsewhere in Europe. Dark Horse published a collection of the first two. In The Land That Time Forgot, Manning changes a few names, but keeps the Burroughs story essentially intact. The storyline is about a theory of “condensed human evolution” in which an individual can evolve from an ape-like creature to a modern human in the space of a single lifetime. In The Pool of Time, Tarzan battles the “weiroos,” a super-race of winged creatures – perfect for the Manning pen and brush.

In England, the stories were published in 1974 by Treasure Hour Books (London) in oversized, hardback editions printed in Italy with excellent production values. The cover of Land has Tarzan dominant, protecting Lya (his leading lady in the story) from the encroaching jaws of a T-Rex. Manning, who was worshipped by ERB fans in Europe, got a cover byline. The frontispiece of this edition, showing a dominant T-Rex fighting two saber-toothed tigers with a smaller Tarzan figure and Lya’s back to the audience, became the cover of the Dark Horse edition.

A note to the collector: The author has seen only the Land edition of the English publications but presumes the other three titles also exist. Nor has the author seen any printings of the last two stories in this series.

Manning is also known as the creator of the excellent series Magnus Robot Fighter for Gold Key. He drew the first twenty-one issues beginning in 1963. Manning passed away of cancer on December 1, 1981 at the Long Beach veteran’s Hospital, leaving behind a legacy of creative genius and a legion of fans.

One wonders how sales of the Gold Key editions might have been affected had they featured Manning’s line art. But virtually all were painted by George Wilson, most carrying a blurb about the story inside. Manning did have a hand in six of the covers, according to the Grand Comics Database. He is credited with the pencils and inks on #159, 160, 163, 164, 166, and 167, with Wilson handling the painted colors.

Some of these issues had a second Gold Key imprint at the bottom of the page with the words:

COLLECTOR’S EDITION

By this time, comics were in the news as collectibles, and the editors wanted to make sure that we fans knew that these comics would some day be old and valuable.

We mentioned that not all the covers were painted. This was the time of the Ron Ely TV series on NBC, and the editors decided to run an occasional “TV ADVENTURES” edition. These appeared in issues #162, 165, 168, and 171. Unlike the awesome movie stills with Lex Barker and Gordon Scott, these photos were cropped at the top and bottom and were not as eye-catching as they should have been. Of these issues, Cazedessus wrote, “These TV-inspired adaptions bumble along as late as 1971, years after the television series itself had ended, and, when the comics finally disappeared, I could only say, Good riddance!”

By the time of the final Ely cover, the comic had been trimmed from Golden Age size to Silver Age size. The cover of #178 carried a large yellow box blaring:

MOST WANTED TARZAN COMIC OF ALL TIME!

By special request we bring you the adaption of Burroughs’ first Tarzan story…

TARZAN OF THE APES!

The interior featured a Russ Manning reprint of the earlier adaption.

In the field of giant editions – Gold Key offered but one entry entitled Tarzan Lord of the Jungle, published in September 1965. It was poorly packaged, contained no special features, and carried Marsh reprints beginning with the inside front cover and all the way to (and including) the back cover. The editors eschewed a painted cover in favor of keeping the costs down – and went with line art by Marsh, showing Tarzan in a tree preparing to do battle with a tiger (or some large cat capable of climbing trees). The covers were of the same newsprint stock as the interior. Every edition I have ever seen says, “second printing” in the indicia, however, Overstreet does not note two printings.

Once Manning had departed the comics, the Gold Key run was coming to a close. The company continued both Tarzan and Korak as regularly published titles with artwork by Alberto Giolitti, Mike Royer, Doug Wildey, Paul Norris, and Dan Spiegle. The run lasted through #206.

The road ahead for Western and its Gold Key imprint was pitted with potholes. Mike Benton writes in The Comic Book In America, “In 1980, faced with diminishing newsstand distribution, Gold Key packaged its comic books three-in-a-bag and offered them to department stores and other non-traditional outlets. In 1981, Gold Key changed its imprint to Whitman.” In 1984, increasing distribution problems killed the comic book line altogether.

Gold Key/Whitman was now gone. Other companies – like Marvel and DC were adapting to the new realities of the marketplace. And Tarzan’s next great artist, Joe Kubert, was waiting in the wings.

Copyright Questions & the Charlton Insurgency

The open question of the copyright status of the Burroughs property resulted in more than one American publisher looking to stick a toe in the water – most famously, the Charlton Comics Group. As Jungle Tales of Tarzan, a Burroughs short story collection, was thought to be in the public domain, Charlton chose that very name for its new publication.

On the cover of the first issue, dated December 1964, Pat Masulli depicted an overly-muscle-bound Tarzan, right hand clutching a vine, staring into the distance, while surrounded by a bevy of jungle animals including a lion, a tiger, various moneys and great apes. The cover blurb stated: “Beginning a great NEW SERIES of the world’s mightiest jungle hero.”

On the inside front cover, Masulli pledged to faithfully adapt the Burroughs stories as he took a swipe at the comics that came before:

“Comic strips about Tarzan have graced our newspapers for years. The first artist to draw Tarzan was Hal Foster. He eventually gave it up to draw his famous ‘Price Valiant.” Burne Hogarth took up where Mr. Foster left off. His powerful renditions of the Ape-Man are some of our comic classics. But what about the Tarzan of comic books?

Masulli continued: “The TRUE flavor of Tarzan as created by Mr. Burroughs has rarely been tasted in comic books. We intend to change that. We intend to be as true to the original as possible. We pledge ourselves to a series of comics that will thrill and inspire, delight and entrance as did the original masterpieces.”

And having set the tone, the first issue, with Sam Glanzman art clearly inspired by Foster and Hogarth, set about fulfilling the promise. Joseph Gill was handling the scripts. The pages were illustrations with machine-lettered captions, adapting two stories from the Burroughs collection, The Capture of Tarzan and The Fight for the Balu*.

*Mangani for “baby”

Tarzan battles a great ape on the cover of #2, an issue that features another letter to the reader from Executive Editor Masulli and two more adaptions by Gill and Glanzman: Tarzan and the Battle for Teeka and Tarzan Rescues the Moon. Issue #3 sported a cover a Dick Giordano and Rocco Mastroserio and two more stories: The Nightmare and The God of Tarzan.

There were some changes in the credits for the fourth and final issue, dated July 1965. The cover – possibly the most eye-catching of the run – was by Masulli and Mastroserio and was a dynamic shot of Tarzan, knife drawn, riding on Numa, the lion. The Lion was the first story adapted in this issue, but, according to a caption on the splash page, the regular artist was unavailable: “Dear friends… Sam Glanzman is away on a much deserved vacation! Bill Montes and Ernie Bache are filling in for him this issue.” The pair also handled the art for the second adaption of the issue, A Jungle Joke.

And that was it for Charlton. After four nicely done issues and eight adaptions, legal pressure ended the run. And though Glanzman was no Russ Manning the issues – all four of them – were nicely done and adhered to the pledge made by the editor at the beginning.

The DC Years

In 1972, when Burroughs was negotiating the rights to its entire catalog to DC Comics, that company had two popular artists from the Golden and Silver Ages that would have been perfect for the job. The one who eventually got the job, Joe Kubert, was a seasoned veteran of DC’s war comics, perhaps best known for his work on Sgt. Rock of Easy Company in Our Army At War. He had done Viking Prince in The Brave and the Bold, and was beloved by superhero fans for his Silver Age revival of Hawkman.

The other artist who might have been considered was Murphy Anderson, DC’s top inker and a fabulous pencil artist as well, whose work enhanced any comic he touched. His inking energized the pencils of many artists from Carmine Infantino on Adam Strange in Mystery In Space, to Gil Kane on Green Lantern, to Curt Swan on Superman. He had taken over the Hawkman feature from Kubert, and did four spectacular solo issues of The Spectre when that Golden Age character was revived in Showcase and in his own title. Though Anderson never drew Tarzan, fans got a bit of a taste of what they were missing in some of DC’s Burroughs companion titles.

Anderson’s amazing splash panel of John Carter of Mars from DC’s Weird Worlds #2, November 1972, is reprinted in black and white in The Life and Art of Murphy Anderson by R.C. Harvey (TwoMorrows Publishing, 2003). The book also reprints a page allegedly from Korak #51, April 1973 (although Anderson is not usually credited with having drawn that issue), showing the son of Tarzan in a classic pose that just as well might’ve been his father. As the author says in the caption, this is as close as Anderson ever came to drawing Tarzan. Anderson’s sleek lines were also about as close as any artist could have come to Russ Manning. There WOULD have been comparisons; but it was not to be.

Joe Kubert was now the man – named editor, writer and artist, he could make of Tarzan what he pleased. And Kubert, like Manning before him, wanted to give the fans an authentic Burroughsian Tarzan. The critics could not have been more pleased. Here’s how Cazedessus put it in “Lords of the Jungle”: “…he was the best choice one could have hoped for. His first issues, starting in April of 1972, showed a strong Foster influence dating as far back as some 1929 sequences. But quickly, Kubert’s own strongly vigorous style asserted itself.”

The late Les Daniels, in his book DC Comics – Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes (Bulfinch Press, 1995), was equally impressed with Kubert’s work:

“…when DC got the rights in 1972, Kubert was ready with a lean, rangy, intense version; his scripts and artwork ranked among the most authentic and effective ever seen.”

The brief Kubert era began in the midst of DC’s experiment with 52-page, 25-cent editions sans a DC “bullet” logo of any type – just a circle about the size of a half-dollar proclaiming:

1st DC ISSUE

The numbering was carried over from Gold Key – so this was officially Tarzan of the Apes #207, April1972. Kubert must have supposed that old fans would want the numbering sequence intact, and newer fans, attracted by the change in cover styles, would be more comfortable with an established title – not exactly the credo of modern comics where #1’s proliferate like rabbits.

The first DC story began in medias res without a logo, title, or credits – but explodes into action on pages two and three with a double-truck, quite dramatic splash across the bottom two-thirds of the page. Here, the familiar Tarzan logo was emblazoned in red with the story title, “Origin of the Ape-Man Book 1” – and then, “From the Novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs.” The splash utilized a favorite design of Kubert’s – a shot of Tarzan, knife in his right hand, being attacked by a panther (in this case), and with his left arm and elbow just under the animal’s chin, fending it off.

He used the exact same pose on the cover, except the animal was an ape. [The pose appears again on the cover of the second Tarzan Limited Collector’s Edition, this time with a lion.]

The story begins Kubert’s expert adaption of Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes that would run for four issues.

Remember, the first three DC issues were 52 pagers, and so something was needed to fill out the back of the books. In #207, there were three extra features, beginning with “The Dum Dum,” the celebration of the Great Apes. This would morph into a letters column, but for this issue, Marv Wolfman presented a bio of ERB. The second feature was interesting: a text feature entitled “Tarzan’s First Christmas” taken from the Sunday page of December 27, 1932 – complete with the Hal Foster art panels.

As a final treat, readers of this first DC issue got a taste of John Carter of Mars, a chapter from ERB’s A Princess of Mars with gorgeous art by Anderson. At the end of the book, we learned that Gray Morrow would illustrate the next chapter. Imagine. Kubert, Anderson and even a single page by Morrow; how would the second DC issue stack up to that?

Pretty well, as it turned out. The Kubert cover to #208 contained less action, but more drama as Tarzan mourns his just-killed “mother” – Kala, the ape who raised him. There follows another Foster story from January 24, 1932, and the Gray Morrow chapter of the John Carter story.

The Dum Dum carried letters, all addressed to Joe, from people who had been provided stats of the first issue in advance of publication. They included Burroughs’ son Hulbert (I personally like your artwork); super-fan Richard Lupoff (I’m quite delighted); Vern Coriell of the Burroughs Bibliophiles (Tarzan fans rejoice…Tarzan is alive and well…safe in the talented hands of someone who cares); and science fiction writer Philip Jose Farmer who nit-picked just a bit (Tarzan’s father was clean-shaven…Tarzan was ten years old, not thirteen when he first entered the cabin). Yessir; Tarzan fans know their hero’s history and you can’t put anything over on them!

The last of the 52-pagers continued the origin story as Tarzan proclaims himself to be not an ape but an M-A-N and battles Terkoz over Jane Porter. The Foster story this time – the final one that DC would use — was from January 10, 1932. The John Carter story was drawn by Anderson, again making us wonder what might have been.

The Dum Dum continued with reaction from two more people associated with ERB in some way. Camille Cazedessus, Jr., from whom we’ve quoted frequently, wrote the lead-off letter to assistant editor Marv Wolfman: “You have done a remarkable job of capturing the flavor of the original Hal Foster strip, with a better balanced action-paced continuity.”

And pro artist Jim Steranko who published two important volumes of The Steranko History of Comics, was effusive in his praise: “Kubert’s style (as it has evolved over the past four years especially) is perfect for the TARZAN strip. It is a style of enormous vitality, of rich textures, of rugged but controlled imagery that tracks up faultlessly with Burroughs’ own energetic style.” High praise indeed from one of the medium’s superstars of the period. The issue finished with a photo gallery of movie Tarzans.

The “4th DC Issue,” and the last to carry that circled blurb was #210 – now back to regular size and priced at 20 cents. Kubert finished out the origin story and The Dum Dum settled into being a regular letters column – but the wonderful Burroughs back-up features were no longer carried in the Tarzan comic.

For his part, Kubert was off and running; the covers were total works of art; and he set about adapting additional stories by Burroughs and a retelling of some of the classic strips. Issues #219-#223 serialized the second novel, The Return of Tarzan. The book continued in this vein through #229, an issue whose Dum Dum carried a letter by one Arlen Schumer of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, who wrote, “To put it mildly, Tarzan is a masterpiece of art and story.” The book’s format, however, was about to change again.

These halcyon days were a roller-coaster ride if you were a fan on a budget. DC’s Tarzan, which had started out at 52 pages for 25 cents, then standard size for 20 cents, was now a whopping 100 pages for 60 cents. This “Super Spectacular” series would last just six issues, #230-235. The drop-dead gorgeous Kubert covers were gone, replaced by smaller Kubert illustrations accompanied by several large (and ugly) panels promoting the contents of the extra pages.

Fans of the book must have been startled. In #230, Kubert did a beautiful contents page, and a 6-page short. That was followed by a Bob Kanigher-scripted story penciled by Kubert but inked by Russ Heath. The fillers included a Russ Manning reprint; Simba the Jungle Boy by George Kashdan with art by Jack Sparling; an early Congo Bill reprint; and finally, “Meet Detective Chimp” written by John Broome with pencils by Carmine Infantino and inks by Frank Giacoia. Every backup story sported a jungle boy/man or a monkey, but it wasn’t Tarzan. In a “special Dum Dum News Flash,” Editorial Assistant Allen Asherman explained:

“Now that TARZAN has been expanded into its 100-page Super-Spectacular size, each issue will feature many surprises, along with stories of your favorite adventure characters. KORAK will be appearing in this magazine. And there’ll be many interesting features about Edgar Rice Burroughs and his creations. So spread the good word, and keep watch for the bigger and better TARZAN.”

Bigger? Well, yes. Better? Not exactly. In the earlier books, the covers alone were worth the price of the comic, but now the covers were not as enticing and many fans probably didn’t care for the older material. Manning reprints and various Congo Bill and Detective Chimp stories continued until #236, when the full-frame Kubert covers resumed. However, fans who might have thought the book was back to its original DC glory must’ve been shocked to look inside and discover that Joe Kubert was not there.

The Dum Dum in #236 was devoted to explaining what was happening to DC’s Tarzan. First, there was a letter from reader Vinc Ellis of Pueblo, Colorado, asking that the format be stabilized with Tarzan as the main feature and “no junk reprints.” Ellis wanted “an honest product, not just a gimmicked marketing package.” That editorial assistant Asherman chose to highlight the letter stems from his own revelation that there were other, similar complaints in the DC mailbag. Agreeing that the book had been through a number of changes, he went on to explain that comics publishing is “…not fully a labor of love,” and “Comics are part of the publishing business, and, as such, various ‘unorthodox attitudes’ are experimented from time to time.” As such, the current issue was back to normal size with a 25-cent price.

In the “Say it ain’t so, Joe” department, Asherman explains the change of artists on the interior story, illustrated (from a Kubert script) by Philippine artist Franc Reyes: “Because of pressing editorial duties, it is no longer possible for Joe Kubert to draw the TARZAN books. However, Joe will still retain the editorial reins, in addition to designing the graphics for the TARZAN books.”

The issue carried a full-page house ad for Kubert’s TOR with a “coming soon” announcement. And to ease the fans’ pain just a tad, he continued to turn in fabulous cover art through issue #249, and one more for good measure on issue #253.

There were more Burroughs adaptions, and Manning reprints; issue #237 was mostly Manning but with what appears to be a new Kubert splash. #238 was a 50-cent giant featuring Manning’s “Return to Pellucidar.” #240 proclaimed “First time adaption of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ last novel: The Castaways.” Kubert was still providing the layouts, but the art was by Reyes. With #243, the art was variously by Rudy Florese or the Redondo Studio.

Issue #250 began an adaption of Tarzan the Untamed. Now scripted by Gerry Conway, the book featured art by Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez and the Redondo Studio and a cover by Lopez and Ricardo Villagran. From this point on, covers were by Garcia-Lopez or Ernie Chua (Chan) except for the Kubert cover on

#253. There were Kubert stories in #252, 253, 257 and 258 (the final issue). The last published DC story was “The Renegades” by Kubert.

During this time, DC held the rights to the other Burroughs properties. While Kubert was concentrating on Tarzan, Joe Orlando was named editor of Korak, Son of Tarzan. Len Wein, and later Robert Kanigher handled the writing. The artwork was by Frank Thorne. Pellucidar and Carson of Venus (for the first time in comics) appeared in the first DC issue with Wein scripts and art by Alan Weiss and Mike Kaluta, respectively. Murphy Anderson drew the Korak stories in #52-56. There were fourteen issues with the numbering continued from the Gold Key series. The book was renamed Tarzan Family with issue #60.

DC also published an anthology title called Weird Worlds that lasted for ten issues. It included John Carter of Mars, brought over from Tarzan #209 and Pellucidar from Korak #46. Both features also ran in Tarzan Family. And one of Burroughs’ later (and most intriguing) novels, Beyond the Farthest Star, was serialized in Tarzan #212-218 and Tarzan Family #16.

In what was a special treat for Kubert fans, DC dedicated two of its Limited Collectors’ Edition treasury-sized books to Tarzan.

The first, #C-22, Fall 1973, represented Joe’s adaption of Tarzan of the Apes from #207-210, but with some differences. In the original printing, Kubert used a “framing sequence” of a safari, hired by a woman searching for her father. A fierce panther attacks them and Tarzan shows up to save the day. The safari leader says to the woman, “I’ve – heard tell of an ape man…but I never believed he actually existed!” He then proceeds to tell the origin story, sounding very much like the narrator in the opening paragraphs of the Burroughs novel. As the man’s story ends, Tarzan swoops down from the trees delivering the woman’s father to her. Perhaps for reasons of space, all that was eliminated from the reprint and a different, full-page splash was substituted. The issue also carried a neat feature on how to draw Tarzan, a Kubert biography, and a table-top diorama on the back cover – making one cringe to think they even suggested cutting this edition up.

The second LCE was #C-29, dated 1974, representing The Return of Tarzan from #219-223 – in the same form of the original publication. It was a spectacular 5-part story that showcased Burroughs’ tale of Opar, the near-sacrifice of Jane Porter, and the High Priestess La – and Kubert’s art in a form more easily appreciated. There wasn’t a lot of room for special features, but Kubert drew a gorgeous contents page, presented in glorious back and white, and there was a short article about SF writer Phillip Jose Farmer’s contention that Tarzan was a real person and was still alive. The back cover was yet another table-top diorama for those fans who had their scissors handy.

Each of the two LCEs was a nice package for a buck – and certainly more exciting and entertaining than some of the reprints we’d seen in the regular run of the title.

DC had put Tarzan fans through a plethora of format changes, price changes, and different creative teams. But from that “1st DC Issue” up until the 100-page Super Spectaculars, it had been a glorious time for Tarzan in comic books. The one disappointment in those early issues was, of course, the production values. With the Dark Horse release of Tarzan: The Joe Kubert Years, fans can now see the artwork in a high-quality presentation.

DC had taken Tarzan well into 1977. But it was time for a change of license, a new artist experienced at drawing barbarians, and a certain Rascally One who also had a great appreciation for the original stories.

The Marvel Age of Tarzan – or – Make Mine Mangani

Of all the Tarzan imitators, perhaps the best and certainly one of the earliest was David Rand also known as Ka-Zar. A thinly disguised version of the Burroughs concept, Rand was not raised by the Great Apes, but by lions. Credited to Bob Byrd, Ka-Zar’s original adventures were all contained in three issues of his own pulp magazine, starting in October 1936. The magazine was published by Martin Goodman, who would go on to be the publisher of Marvel Comics.

In fact Ka-Zar was also an early jungle hero in comics, appearing in Marvel Comics #1, October 1939, and Marvel Mystery Comics #2-5, December 1939 through March 1940. And then for years, the adventures of Ka-Zar went untold until Stan Lee, never one to forget a character with potential, revived him in 1965 in an X-Men story. In the now-legendary Savage Tales #1, May 1971, Roy Thomas explained the revival:

“In the heart of the steaming Antarctic, the mutant X-Men… discover a jungle that time forgot – a snarling sabretooth – and the tiger’s steel-muscled master. Ka-Zar, in his newest, his greatest incarnation. Story by one Stan Lee. Ka-Zar kicks around for a few years — plays second fiddle to Spider-Man, Daredevil, even the X-Men again. He’s drawn by the best in comicdom: Neal Adams, John Romita, Jack Kirby, Gene Colan. Eventually, he gets his own half-a-book series. And now finally: the longest feature in the Premier issue of SAVAGE TALES. ”

Lee’s story, “The Night of the Looter,” was a barnburner. Outside the influence of the Comics Code, Lee was able to feature a beautiful female villain who used her own body as a weapon to defeat the blonde jungle lord. There are even some breast shots in silhouette or with strategically placed strands of hair.

But Ka-Zar, who referred to himself in third person much like Bob Dole, was having none of it. He rebuffed her sexual advances, explaining that he (like Tarzan) was jungle bred but had seen civilization and found it lacking. Wearing its liberal heart on its sleeve, the story explains that Ka-Zar could not condone the hatred of mankind, the polluting of the air and land, or hunting for sport. “I’ve known your civilization, and I spit upon it!” he growled. The femme fatale, Carla, ends up dead, nude, and floating face down in the swamp. “The looters are gone! But the jungle endures forever,” says Ka-Zar to Zabu as the story fades to black.

Stan Lee told an exciting story, and to illustrate it, he chose John Buscema, who would go on to draw more than 200 stories of Conan the Barbarian, and who would become a virtual replacement for Jack Kirby after his departure for DC. Buscema’s art, done in a wash, was dynamic and moved the story along with great action shots of dinosaurs, jungle savages, and tanks. With a little tweak here and there, it could have been a Tarzan story.

Fast forward to June 1997, and suddenly Buscema WAS doing Tarzan – the real thing this time! Marvel had done Ka-Zar complete with its Pellucidar-like lost world theme, and it had done Warrior of Mars – from the Gullivar Jones stories of Edwin Lester Arnold in its anthology title Creatures On the Loose #16-21 (possibly as a reaction to having lost the Burroughs license to DC).

But now, the license belonged to Marvel and Roy Thomas got his chance to script. Thomas decided to return to adaptions, and chose Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar to be the first story in the title, now renamed Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle.

In a text page in the first issue, he explained why he chose that tale, and told the readers that there are certain characters every writer wants a chance to script:

“…I was more than pleased – I was ecstatic – when I learned that Marion Burroughs (daughter-in-law of the late, great ERB) and his grandson Danton Burroughs, who manage the master’s works, had requested that Big John Buscema and I be the team to handle Tarzan’s new illustrated adventures. This was based, we both presumed, on our six-year association with a dissimilar, yet vaguely related creation know as Conan the Barbarian.”

Thomas went on to explain the difficulties of handling the tales of two loin-clothed adventurers – and so, to keep Tarzan authentic – he returned to the novels and stories of ERB. However, except for a retelling of the origin in #2, Thomas intended to avoid retelling the same stories that other comics had recently done. He felt that The Jewels of Opar was the perfect story because it contains all the elements that have come to be associated with Tarzan.

As for his and Buscema’s approach to the character of Tarzan:

“For the most part, we naturally prefer to let the writing and the art speak for itself. John and I like to think we see Tarzan, at least in large part, the way ERB himself saw him. He is a man of two worlds, equally at home in each – yet totally at home in neither. One moment, he is a cultured Englishman, heir to a peerage – the next, he is not merely an uncivilized savage, but a raging jungle beast, as fearsome as Kala, the she-ape who reared him.”

Fans may have wondered what kind of Tarzan Buscema would give them.

Thomas mentioned in that first issue that it was “fairly obvious” that Buscema was influenced by Hal Foster, the first great Tarzan artist. Indeed, but Buscema seemed to want to stay in the Kubert mold – with a muscular yet sleek ape-man and a lush jungle. In fact, Mark Evanier was quoted in Comics Interview as saying Buscema wanted to stay close to the Kubert version. Those fans that missed Kubert’s version could take comfort that Big John ‘s version was closer to Kubert’s than to Manning’s. It might not have been the case in Europe, where Manning was still king, but it was likely the right approach for fans in the United States.

The first issue gave us a dynamic Buscema cover of Tarzan battling a lion – and a more sedate pinup of Tarzan posed in the jungle.

Issue #2 was the “special origin issue and continued on “The Road to Opar.” The great Archie Goodwin was listed in the credits as “consulting editor.” The letters page entitled “Tarzan’s Jungle Drums” debuted with anticipated questions that might come from the fans such as: “How can you show, in 1977, with a clear conscience, a ‘hero’ who battles and slays lions, leopards, apes, etc.? Don’t you know these are all endangered species?” There’s nothing like being pro-active and nipping those still-to-be asked question in the bud!

Issue #3 introduced the High Priestess La with a cover blurb, and the credits informed us that Tony de Zuniga was now inking over Buscema’s pencils. There was also a bonus page of artwork showing Buscema’s early rendition of the ape-man, done as a demonstration of his approach to the character – presumably to show the folks at ERB, Inc.

The letter column in #4 carried the first reactions from fans to the premier issue – and, we learned several things from Roy Thomas. There had been “a torrent of letters and postcards” – and Roy and John had been “especially interested in readers’ first reaction to their premier outing on the ape-man because they had purposely done something a bit different from the usual ‘Marvel-type’ book and from what had been done before with Tarzan.” Roy explained that he and John had taken a more leisurely pacing to develop the feel of the strip rather than trying to squeeze in as many fights, recues and baddies as possible. He also revealed that Buscema had inked the first 2 and a half issues himself, relying on “good” drawing rather than “a lot of” drawing.

The letters were varied, with Stan Timmons of Lafayette, Indiana writing, “I really expected Conan up a tree. Well, I got Tarzan #1 and I had to scrap every nasty comment I had in mind.”

With the rigors of creating monthly comics, it’s hard to keep creative teams consistent, and by issue #7, Rudy Messina had joined Buscema for the artwork on the short story Tarzan Rescues the Moon. Issue #8 featured a pin-up entitled “Tarzan Battles Chulk” with the caption:

Proof positive, if any be needed, that Tarzan is Lord of the

Jungle – and Big John Buscema is one of the greatest

comic-book illustrators ever!

You’ll get no argument there. Refer back to that Ka-Zar story in Savage Tales #1 and just imagine Tarzan, handled in a black and white wash by Buscema!

Up next was “The God of Tarzan,” from Jungle Tales in Issue #9, now with Alfredo Alcala inking. #10 continued the Opar storyline, and concluded it in #11 with “The New York Tribe” assisting on the artwork. Issue #12 featured the inking of Rudy Messina with a pin-up by Buscema and Alcala. Issue #13 had an interesting pin-up. It was an alternate and unused version of the cover of #8 inked by Marvel newcomer Bill Black. The inking revolving door continued with #14 as Klaus Janson came on board.

With issue #15, former rock and roll journalist David (Anthony) Kraft took the helm of the scripting, while Buscema and Janson continued with the art. On the letters page, it was revealed that Roy had moved on to do Thor, and that “Dave the Dude” was brought into handle dialoguing and that he would soon take Tarzan to Pellucidar. The “Dude,” interestingly enough, went on to become the literary agent for the literary estate of pulp author Otis Adelbert Kline – a contemporary of Burroughs’ who also wrote stories about Mars, Venus and jungle adventures. (And with whom Burroughs MAY have had an ongoing rivalry!)

The original creative team was gone with issue #19, but there was still a Buscema on pencils – John’s younger brother, Sal. Janson continued to ink, but the team changed even more drastically with #20. Now, Kraft was plotting, Bill Mantlo was scripting and Sal Buscema was inked by Bob Hall.

Fans may have noticed a distinct change in style for the cover of Tarzan Lord of the Jungle #20. Up until this point, every Marvel issue had been penciled by John Buscema, with several being self-inked. A variety of other embellishers had been brought in up though #19: Dave Cockrum (#3); Pablo Marcos (#5); Alfredo Alcala (#9); Tony de Zuniga (#10, 13); Neal Adams (#11,12); Ernie Chan (#14); Josef Rubinstein (#15); Bob McLeod (#16, 18); Klaus Janson (#17); and Joe Sinnott (#19). Cockrum did the pencils on #20, with McLeod on inks.

Finishing out the cover credits, John Buscema was back for a few more covers with inker Bob McLeod (#21, 23, 24, 28); Big John penciled #22 and either he or Bob Hall did the inks; Rich Buckler and Bob McLeod (#25, 26, 27); and the final issue is in dispute. John or Sal, or possibly Bob Layton drew it – or maybe more than one of them did – with Bob McLeod inks.

Issue #21 had Rudy Nebres inking Sal Buscema, and #21 brought in Jim Mooney. Mantlo was, by now, getting full writing credit. Issue #23 had Pablo Marcos on inks; #24, 25, and 26 had Bob Hall; #27 and 28 had Ricardo Villamonte; and #29, the final Marvel issue, had P. Craig Russell on inks.

Unlike DC, Marvel had not put Tarzan fans through a multitude of format changes – but, like DC, it had not been able to keep the creative team stable through the run. Marvel had also done less with the other Burroughs properties, though it did publish twenty-eight issues of John Carter, Warlord of Mars.

Marvel also published three annuals. The first, dated 1977 featured an impressive cover by Big John, and two adaptions from Jungle Tales of Tarzan by Thomas, Buscema and inker Steve Gan. The 1978 edition had a mysterious cover by John Buscema and Bob Hall and a 33-page story by Mantlo, Sal Buscema and Fran Matera. The 1979 edition had a cover by Buckler and McLeod with another long Mantlo story inside. Sal Buscema and Ricardo Villamonte penciled and Joe Sinnott inked.

Like DC, Marvel’s Tarzan was hampered by the cheap paper and printing that all the companies used to keep the cover price down. Marvel had started the run at 30 cents and had seen it escalate a dime over the course of twenty-nine issues. But Marvel did publish one Tarzan edition with excellent production values. It was a Tarzan of the Apes one-shot published in a magazine format in 1983 as Marvel Super Special #29.

The script, by Sharman DiVono and Mark Evanier, was yet another adaption of the first Burroughs novel – this time with art by Dan Spiegle, who had previous experience on ERB properties at Western/Gold Key. This must have been a labor of love for Spiegle as his artwork is detailed with creative panel arrangements, full-page illustrations, and lush jungles. His characters carry emotion – see Kala the she-ape weeping over her dead balu – and his Tarzan is impressive, all the way from infant to jungle king. The final sequence of Tarzan in a battle to the death with the ape Kerchak ends with Spiegle’s full-page panel of the ape-man beating his chest in victory. The colors really popped in this edition, giving Spiegle an advantage that the Buscema brothers never had.

Front and back covers were done by the painter Charles Ren, who also did covers for the 2-issue limited series that reprinted the book in a regular comic book format in July and August 1984. By the way, Sharman DiVono is a science fiction novelist and short story writer who has published several stories of the Silver Surfer. She has also written Duck Tales for television.

So how did Marvel’s Tarzan stack up when compared to comic book versions that came before? Very well in the early going, but as the fans learned with Kubert and DC, it’s difficult to hang onto those writers and artists that we become accustomed to. When the writers, pencilers, and inkers shift from issue to issue, the quality will fluctuate.

In April 1983, in a piece in Comics Interview, Mark Evanier discussed the difficulties of pleasing everyone – including the foreign markets:

“… the whole Marvel deal was doomed from the start. … The foreign publishers did not want adaptations. Roy Thomas felt they should do adaptations. They wanted the Russ Manning versions, but John Buscema wanted to make it as much like the Joe Kubert version as possible. Also, the foreign publishers needed stories in fifteen-page increments, because most of the books feature thirty pages of material and two pages of ads. Everything that made the books commercial in America, made them uncommercial overseas.”

Tarzan had clearly been a labor of love for Roy Thomas and John Buscema – and undoubtedly others at the House of Ideas as well. But as they have always done, the ERB properties moved on. The Marvel Age of Tarzan was over.

Tarzan in the 21st Century

Tarzan did not have a regular publisher after the Marvel run ended until Dark Horse took the license in July 1996. But Tarzan still showed up here and there, most notably in some excellent mini series from Malibu Comics. Dark Horse has published a regular series, and many mini series teaming Tarzan with other Burroughs characters, Batman, Superman, Catwoman – you name it – and two issues of Disney’s Tarzan. Alan Moore referenced him in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Most recently, Dynamite Entertainment has published Lord of the Jungle, with yet another adaption of the first Burroughs novel. And the Dark Horse Tarzan Archive series brings his adventures to a new generation.

We’re well into a new century with wonders once predicted by science fiction and comic book writers now a part of everyday life! And yet, there’s something about a boy, orphaned in the jungle, who becomes King of the Great Apes that still excites, still resonates. Even today, Tarzan is an icon, famous the world over. He is still the Lord of the Jungle, the King of All Media, and his stories will be told forever.

THE END

About the author:

Lynn Woolley is a lifelong comic book fan and collector based in Central Texas. He is the author of several books including Warner Bros. Television (McFarland 1986) and a memoir, The Last Great Days of Radio (Republic of Texas Press, 1994). His short story “A Stitch in Time” appeared in the November 1980 issue of Amazing Stories, and another short, “Made In USA,” appeared in Shadows Of… in Spring, 1982. Watch for his fortcoming collection “The Clock Tower and Other Stories.” For reprint rights to this article email lwoolley9189@gmail.com.