Texas Sees Rise in Local Government Spending Fever, Affluenza Outbreaks; Bell County No Exception

In our (hopefully) post-pandemic world, a new affliction is emerging, and unsustainable spending is its most visible symptom. This affliction is a fever, a spending fever and most hard hit are local governments still reeling from recent election cycles in which efforts to procure voter approval of new bond projects (also known as tax increases) were dampened if not totally halted.

Bell County Justice Center. Photo by Lou Ann Anderson for WBDaily.

From school districts to cities, from counties to community and junior colleges, many entities recognized how a virus positioned as a public health crisis, accompanied by lockdowns and followed by subsequent and predictably dire consequences made for a less-than-ideal time to seek more of taxpayers’ hard-earned dollars to fund new government projects.

So where does that leave us?

Cue the affluenza surge

For our general purposes, affluenza is “a social condition that arises from the desire to be more wealthy or successful.” It similarly applies when defined as “the inability of an individual to understand the consequences of their actions because of their social status or economic privilege.” An individual or perhaps an entity (i.e., government) viewing itself as possessing a high degree of social prominence and immunity from real accountability?

More specifically applied to government, fiscal affluenza appears to be a somewhat chronic condition in which local elected officials and associated bureaucrats rotate through an endless stream of “asks” seeking new dollars from taxpayers. Problems, however, surface as these theoretical upgrades to local government facilities, operations or other organizational accoutrements compound the debt burden carried by taxpayers while not necessarily yielding a good return rate or perceivable benefit based on the funds invested.

Governments embrace affluenza at taxpayer expense

In having no doubt that 2022 will bring more local government “asks,” I decided to look at current debt levels in my local area of Bell County. While this information will focus on larger Bell County entities, data sources are included such that any Texas taxpayer can create their own local debt level profile.

But first, let’s start with the bigger picture and work our way to the local level. According to the U.S. Debt Clock, the U.S. National Debt sits at nearly $30 trillion. That translates to $89,000+ of debt per citizen, nearly $238,000 per taxpayer.

When the Texas Bond Review Board recently provided numbers for FY 2021 (Sept. 1, 2020 through Aug. 31, 2021), we learned that Texas taxpayers now have local government debt – debt from cities, counties, school districts, community/junior colleges and special districts – totaling $389.7 billion, a $14 billion increase from FY 2020. Per the Texas Public Policy Foundation, “On a per capita basis, local governments have now borrowed so much that each man, woman, and child in the Lone Star State effectively owes $13,500 for his or her share.”

TPPF further notes:

Of course, massive indebtedness is not without consequence. Texas’ local government borrowing binge is setting the stage to “saddle future generations with enormous obligations, unleash higher taxes, slow economic growth and business investment, and trigger credit rating downgrades.”

In its analysis of this information, The Texan identifies school districts as accounting for the majority of Texas accumulated local government debt. It further notes that ISDs collectively saw a slight increase from last year’s numbers while cities’ outstanding debt fell substantially.

The Texan also cites how since “cities and school districts are more numerous than the other taxing entities, they also hold more debt per capita than the others” and that “18 of the top 20 localities in terms of outstanding debt are either cities or ISDs.”

Let’s get local

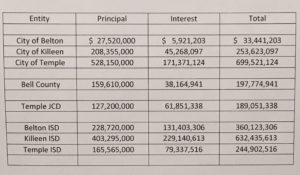

With that backdrop, what kind of debt service are taxpayers responsible for when it comes to the Bell County local governments? Listed below are the county’s larger entities.

And it’s important to note how government entities use bond campaigns to purposefully talk only about principal, but with no interest mentioned. It makes the “ask” look better. Interest is additional debt accrued due to the cost of borrowing money and, with bonds, is often an additional 40 to 50% of the principal. These figures incorporate interest into the debt perspective and as you can see, figures without interest (principal only) create a deceptive view of real debt levels.

Bell County Area Local Government Bond Debt (FY 2021)

Using this data, many Bell County residents can determine their total local government debt burdens. For instance, taxpayers living in the City of Belton, Bell County, Belton ISD and Temple JCD have a total debt level of $780.4 million. Taxpayers living in the City of Killeen, Bell County and Killeen ISD have a total debt level of $1.08 billion. Taxpayers living in the City of Temple, Bell County, Temple ISD and Temple JCD have a total debt level of $1.33 billion.

Obviously, these cities support populations of varying size as also do the school districts such that context is required for further in-depth analysis. For instance, Belton ISD has 13,000+ students with 1,600+ employees (teachers and staff). Killeen ISD has 45,000+ students with 6,100+ employees while Temple ISD has 8,700+ students with 1,300+ employees.

These numbers do, however, well illustrate the difference that interest makes in calculating the real numbers when voters are asked to approve new bond debt. During Temple College’s May 2021 bond election, the advertised bond amount was $124.9 million. When speaking about that election, I discussed how local entities are disingenuous with voters as they use a principal only amount in bond election campaign materials opposed to using an amount that is principal plus estimated interest.

In the case of Temple College, my prediction was for the $124.9 million bond package to include approximately $50 million of interest (based on a 40% projection) for a total of closer to $175 million. Per Texas Bond Review Board, the bond issued includes a lowered principal amount of nearly $110 million principal (roughly $15 million less than what was approved), but $60 million interest for a total of $170 million. Undoubtedly $125 million is quite different from $170 million and reminds that the bond package numbers advertised are rarely reflective of what packages’ approval will truly cost taxpayers.

Do your homework

This article is a prequel to upcoming bond elections. The information presented here is in part to arm taxpayers with the tools to determine their local government debt load. As we move toward the next affluenza spending “ask” (probably in May), this knowledge becomes critically important – especially since our country’s current economic malaise shows little if any signs of relief.

Data for all local government entities is available using the Texas Bond Review Board Database Search. From this page, click on the Debt Tab/Searchable Databases/Local Debt Outstanding. Select the Fiscal Year and Issuer Type (City, Community/Junior College District, County, etc.) and from there select your specific entity.

Governments don’t necessarily want taxpayers to know what’s being done in their name, with their dollars or at their alleged behest. With that, arming yourself and sharing this knowledge is the best path toward breaking spending fevers and quelling affluenza surges so as to ensure a healthy degree of fiscal responsibility within our local governments.

Lou Ann Anderson worked in central Texas talk radio as both a host and producer and currently hosts Political Pursuits: The Podcast. Her tenure as Watchdog Wire–Texas editor involved covering state news and coordinating the site’s citizen journalist network. As a past Policy Analyst with Americans for Prosperity–Texas, Lou Ann wrote and spoke on a variety of issues including the growing issue of probate abuse in which wills, trusts, guardianships and powers of attorney are used to loot assets from intended heirs or beneficiaries.